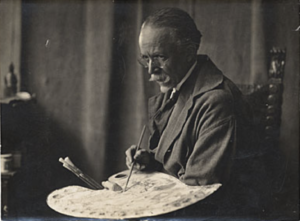

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) was an African-American painter whose work merits more attention than it receives. He was the son of a Methodist minister. His second name was given in recognition of Osawatomie Kansas – where John Brown had a violent encounter with pro-slavery advocates in 1856. Though bearing a name that marked the reality of racial tensions – his art never picked up this theme. Instead his art sought to provide a record of life for the African – America and it was also a means for him to express his deep Christian faith – specifically in creating paintings of biblical stories that captured his sense of those narratives.

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) was an African-American painter whose work merits more attention than it receives. He was the son of a Methodist minister. His second name was given in recognition of Osawatomie Kansas – where John Brown had a violent encounter with pro-slavery advocates in 1856. Though bearing a name that marked the reality of racial tensions – his art never picked up this theme. Instead his art sought to provide a record of life for the African – America and it was also a means for him to express his deep Christian faith – specifically in creating paintings of biblical stories that captured his sense of those narratives.

Since first seeing The Banjo Lesson several years ago I have been moved by its simplicity, its grace and the beauty of the relationship it expresses. The occasion for this work is a chapter in Tanner’s life when he was in Paris studying art and took ill with typhoid and returned to America.

On his return he was encouraged to spend some time in the mountains for health reasons. While visiting the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina he gained fresh insight when discovering the reality of poverty among his fellow African Americans. He had grown up in Pittsburgh in a community of the well-educated and financially comfortable. The photographs he took while on that visit to the mountains became the inspiration for The Banjo Lesson. The painting first came to public attention as an illustration for a magazine story –Uncle Tim’s Compromise on Christmas where a grandfather gifts a grandson with his most favoured possession – his banjo.

Tanner has expressed well the dignity of the figures bringing together two generations bound by love and attentiveness. Set in a simple context that gives the viewer a glimpse into the life of the characters: rustic, spare, hard-working and deeply human – buoyed up by the hopeful s trains of music.

trains of music.

In our divided world we do well to attend to the themes captured by this artist. Themes no doubt rooted in his Methodist- Episcopal upbringing where it is understood that humanity will flourish only where dignity and love are embraced. At a time when divisions dominate, suffering afflicts, uncertainties abound and hope erodes, the gentle scene in this painting offers comfort for troubled times.

In depicting narratives from the bible – Tanner reveals his spiritual sensitivity as found for example in his rendering of the well-known encounter between Nicodemus and Jesus. A night-time visit at an out-of-the-way location where Nicodemus asks a number of questions including that most primordial of questions about his own salvation. Tanner’s masterful engagement of light and dark impacts the emotions of the viewer while for the artist light served to symbolize the good.

Visual art can be a stepping stone out of an unsettling world and into a world that reminds us to be grateful and compassionate. It can also nudge us to consider themes that take us beyond the confines of our immediate experience and invite us to participate in the “poetry of seeing”.

The story of Nicode mus in John 3 includes not only the questions but also a comment as poignant for our times as it was when originally uttered. “The wind blows where it likes, you can hear the sound of it but you have no idea where it comes from or where it goes.

mus in John 3 includes not only the questions but also a comment as poignant for our times as it was when originally uttered. “The wind blows where it likes, you can hear the sound of it but you have no idea where it comes from or where it goes.

Nor can you tell how a person is born by the wind of the Spirit.” (John 3:8 – J.B. Phillips translation) There is a modern prophet who had his own take on our questions and where we will find the answers – and it has echoes of these gospel words.

Blowin’ in the Wind

How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

How many seas must a white dove sail

Before she sleeps in the sand?

Yes, and how many times must the cannonballs fly

Before they’re forever banned?The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the windYes, and how many years must a mountain exist

Before it is washed to the sea?

And how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the windYes, and how many times must a man look up

Before he can see the sky?

And how many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry?

Yes, and how many deaths will it take ’til he knows

That too many people have died?The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind— Bob Dylan (1963)

We are grateful for those who provide financial support for the work of IMAGO. Donations may be mailed to IMAGO 630 Indian Road, Toronto, ON M6P 2C6 or Donate Here ONLINE